How Much is Too Much? Scientists Show Freshwater "Tipping Points" for MS Sound

March 25, 2024

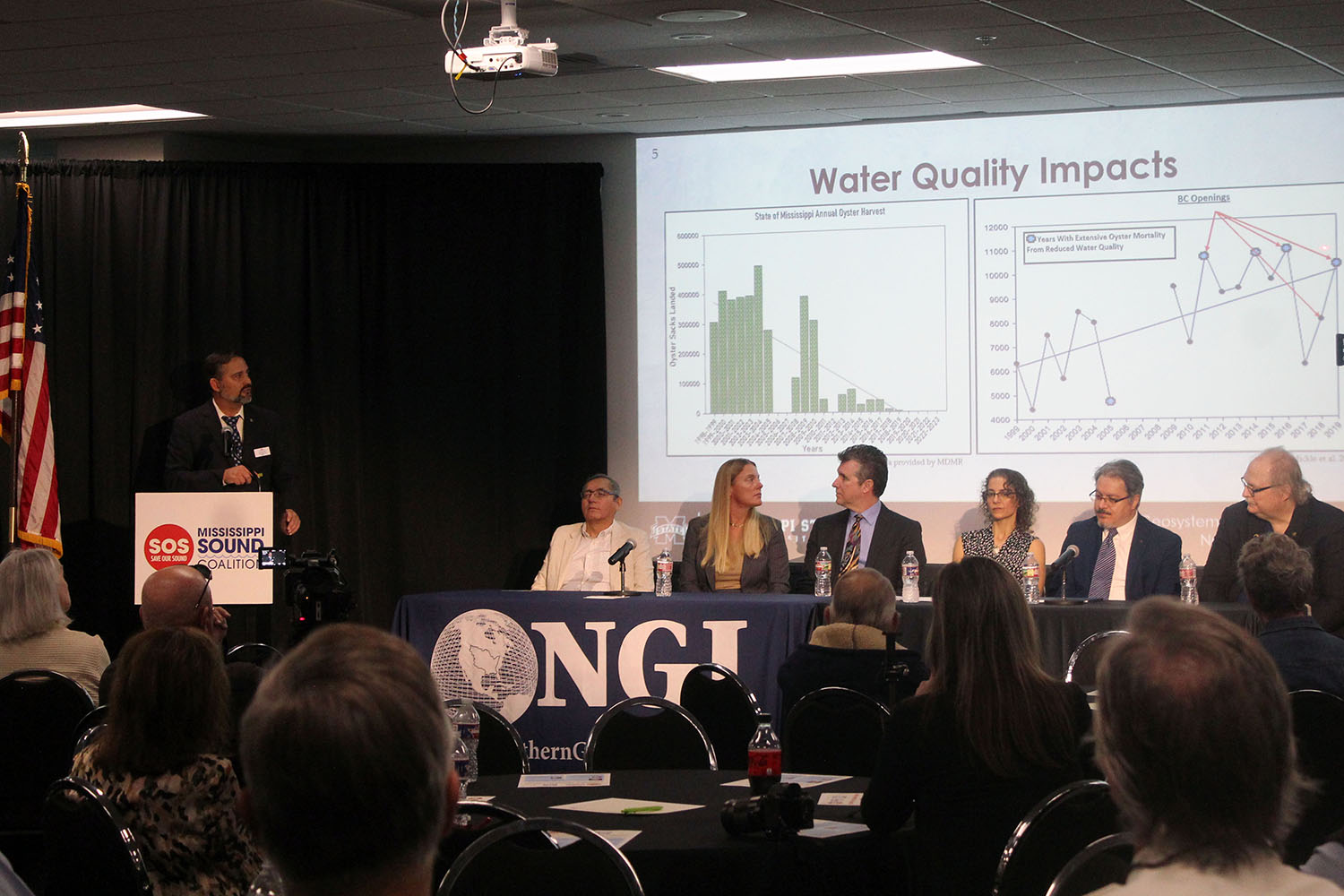

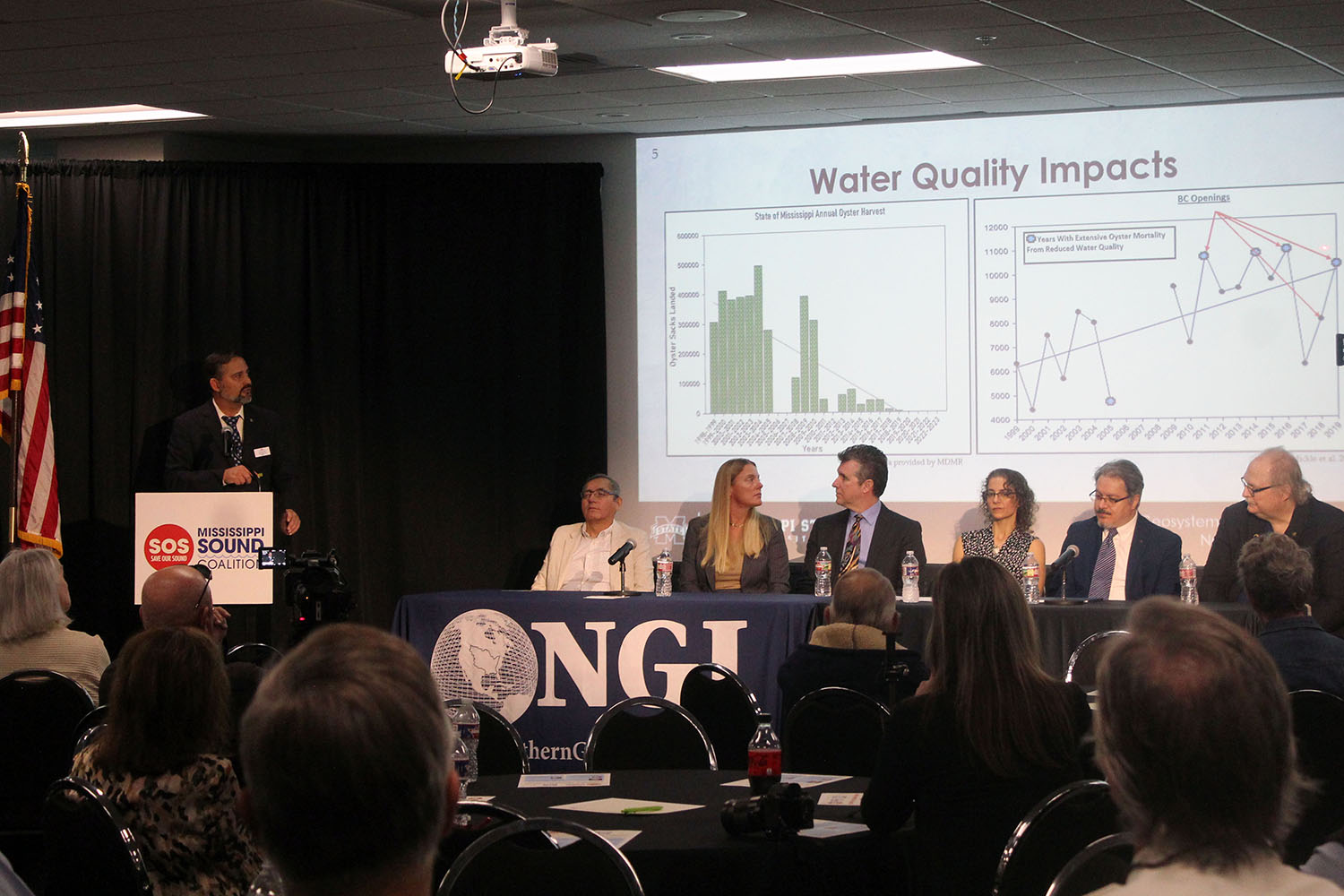

Dr. Paul Mickle, Co-Director of the Northern Gulf Institute, moderates the Mississippi Sound Coalition Scientific Research Forum. Scientists from Mississippi State University and the University of Southern Mississippi discussed computer modelling of ecological impacts from Bonne Carre Spillway operations. Credit: Sarah Brown, MSU

The Mississippi Sound Coalition, which seeks to restore the Sound and the seafood and tourism economies that depend on it, hosted a public forum on March 14, 2024, to present research that evaluates impacts on it from Bonne Carre Spillway (BCS) openings.

"After years of research, we are now at the point of producing a report capable of impacting policy directly," said event moderator Dr. Paul Mickle, co-Director of the Northern Gulf Institute (NGI) at Mississippi State University (MSU). "We identify tipping points or thresholds for when freshwater from BCS operations start to impact aquatic organisms in the MS Sound. This research can help local and state leaders work with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and provide support to operate the BCS for flood control and account for ecological impacts."

Dr. Mickle led a discussion by the Western Sound Science Collaborative, consisting of seven professors at two Mississippi universities, who were awarded a competitive Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act (GOMESA) grant. "This is a highly respected group of scientists with a total of 227 peer-reviewed scientific journal publications," said Mickle. "There are great modelers in the Gulf, but no state has six modelers of this caliber; We recognize the administrators at MSU and the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) and the funding agencies that allow a team like this to exist."

In addition to Dr. Mickle, presenters at this forum included USM Division of Marine Science researchers Dr. Jerry Wiggert, Professor; Dr. Kemal Cambazoglu, Assistant Professor; Dr. Scott Milroy, Associate Professor; and Brandy Armstrong, Research Scientist; from USM Division of Coastal Sciences Dr. Kim de Mutsert, Associate Professor; and from MSU NGI Dr. Vladimir Alarcon, Assistant Research Professor. After Mickle provided some background on BCS operations, the panel described their modeling efforts and the information that they produce, followed by a question-and-answer session.

The forum's host, the MS Sound Coalition, is led by MS Gulf Coast leaders Gerald Blessey, attorney and former Biloxi Mayor; Dr. Marlin Ladner, President of Harrison County Board of Supervisors; Robert Wiygul, attorney; and Dr. Moby Solangi, Executive Director of the Institute for Marine Mammal Studies. The Coalition works collaboratively with the offices of the MS Governor, Attorney General, Lt. Governor, Secretary of State, Department of Environmental Quality, Department of Marine Resources, Senators, Congressmen, Legislators, and others who can assist in restoring and protecting the MS Sound.

Representatives from local and state offices in attendance included Chris Vignes, Southern Regional Field Representative for Senator Roger Wicker; Win Ellington, Southern Regional Field Representative for Senator Cindy Hyde-Smith; Julie Miller for Congressman Mike Ezell; Ken Taylor, District 3 Jackson County Board of Supervisors; Councilman Kenny Glavan, City of Biloxi; and Al Gumbos, Director of Municipal Operations and Projects for the City of D'Iberville.

Gearld Blessey with the Mississippi Sound Coalition introduces Dr. Paul Mickle, Co-Director of the Northern Gulf Institute, as moderator of the Scientific Research Forum. Scientists from two Mississippi universities discussed impacts on aquatic organisms from Bonne Carre Spillway operations. Credit: Sarah Brown, MSU

The BCS is one of several flood control structures on the lower MS River that came about after the Great MS Flood in 1927, when congress enacted the Flood Control Act of 1928 that diverts flood waters to nearby basins and lakes for protection of life and property. The BCS structure is positioned about 12 miles from New Orleans, Louisiana, and diverts MS River water into Lake Pontchartrain that flows into the Rigolets and Lake Borgne, which connects with the MS Sound.

The expectation was for BCS openings to occur about once every 10 years, and for decades this has successfully protected the New Orleans area without significant harm to nearby estuaries. However, there has been a trend of more frequent openings that push freshwater into the MS Sound's estuarine environment with disastrous effects on its aquatic life, such as oysters, shrimp, fish, and marine mammals.

"In 2011, there was a turning point for oyster biomass" explained Mickle. "But in 2019, there was a double BCS opening that pushed the largest amount of freshwater over the longest amount of time into the MS Sound, and that was pretty much the end. We haven't had a measurable harvest of wild oysters since." He also said unprecedented levels of cyanotoxins associated with harmful algal blooms were documented from Lake Pontchartrain into the MS Sound and across to Jackson County, MS.

Research

There are many environmental factors that negatively impact the Sound's ecological health; however, the leading factor is man-made. "Our paper argues that BCS openings cause the highest amount of variability in the MS Sound," explained Mickle. "Up to now, no one has looked at how much freshwater the MS Sound can take, at what month, at what temperature, and during what spawning season. These are the things we are looking at."

The scientists with USM described an integrated framework of three models that work together to identify and visualize locations in the MS Sound where salinity and habitat are affected and determine tipping points for oyster mortality from BCS openings. These models exchange information, with each one producing specific results that contribute to a broad picture of why and how BCS openings affect oysters.

"The ocean modelling is a backbone effort by Dr. Cambazoglu, Ms. Armstrong, and myself that supports the work of Dr. Milroy and Dr. de Mutsert," explained Dr. Jerry Wiggert. "The aggregate amount of water released in 2019 was effectively six times the volume of Lake Pontchartrain. That much fresh water must go somewhere, and our model can provide an understanding of how it is distributed."

The hydrodynamic model allows them to depict freshwater plume exchanges within the inner shelf, which BCS openings can greatly modify, and give the hydrographic output that drives ecological impacts, such as changes in salinity levels. This model's output is then used by Dr. Scott Milroy to evaluate the suitability of habitat conditions for oyster production and growth, which in turn gives information for Dr. Kim de Mutsert to determine oyster mortality with a marine ecosystem model.

Dr. Kemal Cambazoglu explained that the ocean model allows scientists to do controlled experiments with a tracer to track water from the BCS under the effects of winds, atmospheric conditions, and currents. "We can simulate the circulation within the estuarine system. When running twin experiments, we can switch BCS openings on and off and see how salinity, one of the biggest stressors on oysters, along with other physical parameters are affected in the MS Sound."

Wiggert demonstrated an animation of the model simulation for the 2019 BCS openings, "You can see the waters go into Lake Pontchartrain and progress into and across the MS Sound and reach the Bight as well as Mobile Bay. The whole system starts to respond immediately. This shows that within a day of the BCS opening, the Pearl River plume starts to adjust its trajectory."

Presenters with the University of Southern Mississippi at the Mississippi Sound Coalition's Scientific Research Forum (L-R): Dr. Kim de Mutsert, Dr. Scott Milroy, Ms. Brandy Armstrong, Dr. Kemal Cambazoglu, and Dr. Jerry Wiggert. (Not pictured is presenter Dr. Vladimir Alarcon with Mississippi State University). Credit: Sarah Brown, MSU

Dr. Milroy described how the habitat suitability model uses the hydrodynamic model's output, "My side of the coin is looking at how oysters would perform under these circumstances from the perspective of how changing water quality affects oyster habitat rather than the organism itself." He looks at water quality parameters that the ocean model generates when freshwater from the BCS affects salinity levels and visualizes impacts on the suitability of the habitat for oysters.

"These organisms have been studied for decades by hundreds of researchers all over the Gulf of Mexico and eastern seaboard, and their natural sensitivities to salinity are pretty well known and documented in scientific literature," explained Milroy. "We can show environmental thresholds and visualize what those tipping points look like by creating stoplight patterns that show green zones with temperature and salinity where oysters would really flourish, yellow zones are fair where we start to see warning signs, and red zones are where we're really in trouble when looking at habitat suitability for oysters."

The marine ecosystem model comes into play at this point to understand more complex questions about oyster growth and mortality, "I take all the information from the other models and model the populations of the oysters," explained Dr. de Mutsert. "We can evaluate effects on the actual species, looking at biomass changes, changes in survival and mortality that occur in response to conditions. Other species are included to simulate the environment more realistically."

Dr. de Mutsert explained that the model can isolate cause and effect, "There is a lot going on in the MS Sound. If we want to know if BCS openings caused oyster mortality in 2019 or if the higher river inflow was enough to do that, we can turn the BCS opening off in the simulated environment and compare the oyster biomass mortality to see what we have in those two situations. By reducing the time that the BCS is open, we can determine the point when oyster mortality falls within the natural range and the point when mortality is significantly more than what would have naturally occurred."

The scientists with MSU described their nutrient transport model, which is currently in development, that will identify tipping points from BCS openings that affect the overall health of the MS Sound, such as harmful algal blooms influenced by nitrogen, phosphorus, and chlorophyll-a, as well as seafood health influenced by salinity.

"Since we are building this model from the bottom up, we start with analyzing historical observed nutrient data in the MS Sound and MS River," explained Dr. Vladimir Alarcon. "After that, we will develop a conceptual model and a computational model, which will be calibrated and validated, and then it will be ready for running water quality scenarios or predictions. Our model will be able to tell us if nutrients from the MS River are being transported through Lake Pontchartrain and into the MS Sound."

At the Mississippi Sound Coalition's Scientific Research Forum, Dr. Kim de Mutsert, with the University of Southern Mississippi Division of Coastal Sciences, discusses how a marine ecosystem model is used to understand impacts on oyster growth and mortality from Bonne Carre Spillway operations. Credit: Sarah Brown, MSU

Dr. Alarcon has analyzed and plotted data on water quality and turbidity from stations along the MS Gulf Coast and MS River, with preliminary indications of episodic variations in concentrations in the MS Sound that could result in eutrophic conditions that contribute to harmful algal blooms and dead zones.

"If we want to ascertain the effect of the BCS openings on water quality in the MS sound, we need continuous water quality monitoring," explained Alarcon. "To model nutrient transport, we need, ideally, daily monitoring of water quality before, during, and after at least one opening so that we can develop a reliable model."

The models described by the scientists at MSU and USM will support each other's findings by increasing confidence in the individual models' outputs.

Discussion

The question-and-answer session covered a wide variety of topics, from the scope and factors that the models account for and their data needs to related research efforts, other spillway operations, and seafood safety.

The panel confirmed that the domain area for the models goes from Louisiana's marshes to Alabama's Mobile Bay and can account for changes in rainfall amounts that affect flood conditions. Regarding monitoring data needed, the team identified the Rigolets as a top priority for a gauge station that collects continuous data, and Dr. Mickle indicated that an effort is underway to make that happen.

Dr. Mickle addressed questions about impacts on the MS Sound from the proposed mid-Breton Sound Sediment Diversion project, explaining that this team and their models studied this, they found impacts, and the report is available on the MS Department of Marine Resources website. Dr. Wiggert addressed a follow-up concern about impacts from co-occurring events such as the 2019 BCS openings and mid-Breton Sound Diversion operations happening at the same time. He explained that this scenario was run and showed that impacts from the 2019 BCS openings were so profound that it blocked the mid Breton release from propagating into the western Sound. However, if the BCS were not opened, the mid Brenton Sound Diversion operations could influence bottom salinity and affect oyster reefs. He also mentioned that results from Dr. Milroy's analysis of impacts from the mid-Breton Sound Diversion operations on habitat suitability for oysters and brown shrimp are currently being reviewed and should be available to the public soon.

Regarding use of the Morganza spillway, which is situated farther west to protect Baton Rouge, to reduce freshwater impacts on the MS Sound, Dr. Mickle said that a modeler in Louisiana explored scenarios of operating both structures in concert and found that water coming out of the BCS could be reduced and potentially lessen impacts to the MS Sound. He elaborated that once the USM team's analyses have confidently identified the key tipping points in MS Sound resulting from BCS openings, then that science can be added to conversations about approaches to policy change. Toward that end, Dr. Cambazoglu noted that their model can be used to run scenarios that explore how adjusting BCS openings could alter environmental and ecological impacts on the MS Sound, thus contributing to science-based guidance on modifying operational practice.

When asked about what consumers need to know about seafood safety being affected by BCS impacts, Dr. Mickle said that during 2019, seafood was heavily tested. He explained that since the American regulatory process of seafood safety is the strictest in the entire world, when restaurants and stores offer seafood from the U.S., it is safe to eat.

During the Mississippi Sound Coalition's Scientific Research Forum, Dr. Vladimir Alarcon, with the Northern Gulf Institute at Mississippi State University, answers a question about modeling impacts from Bonne Carre Spillway operations on water quality. Credit: Sarah Brown, MSU

The timeline for completing scenario runs for the integrated modeling framework in 2024 is January to June for the ocean model, June to August for the habitat suitability model, and August to December for the marine ecosystem model. Report writing and reviews start in January 2025, and a peer-reviewed report will be delivered by June 2025.

In conclusion, Dr. Mickle reiterated that the U.S Army Corps of Engineers operates the BCS for the protection of life and property under congressional methodologies provided to them, and that is what they have done. The goal, he said, is to add a third component to their charge: minimize ecological impacts. "When you lose 95% of your total production of oysters as we did in 2019, you're starting over. It can take more than 10 years to get multiple age classes of oysters and oyster reefs to bounce back. We must understand what the MS Sound can take and not let that happen again."

Mickle noted that there have been past BCS openings where impacts have been minimal to nil. "So, it is possible. We know what water quality we need, and the models will help us determine how much water to release from the BCS. We have strong science and tools that can be used to identify a path forward for BCS operations that protect life and property and the MS Sound by minimizing or eliminating ecological impacts."

Slides from this forum will be available on the MS Sound Coalition website.

************

The Mississippi Sound Coalition seeks to restore the Sound and the seafood and tourism economies that depend on it by advocating for policy change at state and federal levels to prevent future damage from Mississippi River waters.

The

Northern Gulf Institute is a NOAA Cooperative Institute with six academic institutions located across the US Gulf Coast states, conducting research and outreach on the interconnections among Gulf of Mexico ecosystems for informed decision making.

By

Nilde Maggie Dannreuther, the Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University.